The holiday season tells a story of abundance. But for families like mine growing up in New Orleans, it was a season of stretching what little we had. SNAP never covered enough, and my high school job at McDonald’s sometimes determined how much food would be on our table. While other kids hung out, I would scoop fries until 11 PM, the latest a 16-year-old in Louisiana could work.

I did not understand then that I was lucky. Lucky to have a job within walking distance. Lucky to have a grocery store close by. Lucky that my school grades didn’t slip. Lucky that my home life bent but didn’t break.

In my job today, I tell the stories of children who do not enjoy the same luck I did. They are pulled into the legal system rarely because they are violent, but because they are struggling to survive, often turning to crime to meet the basic needs that their families can’t. This is especially true during the holiday season, when many families face higher food costs, school closures, and the pressure to provide in a moment that celebrates excess.

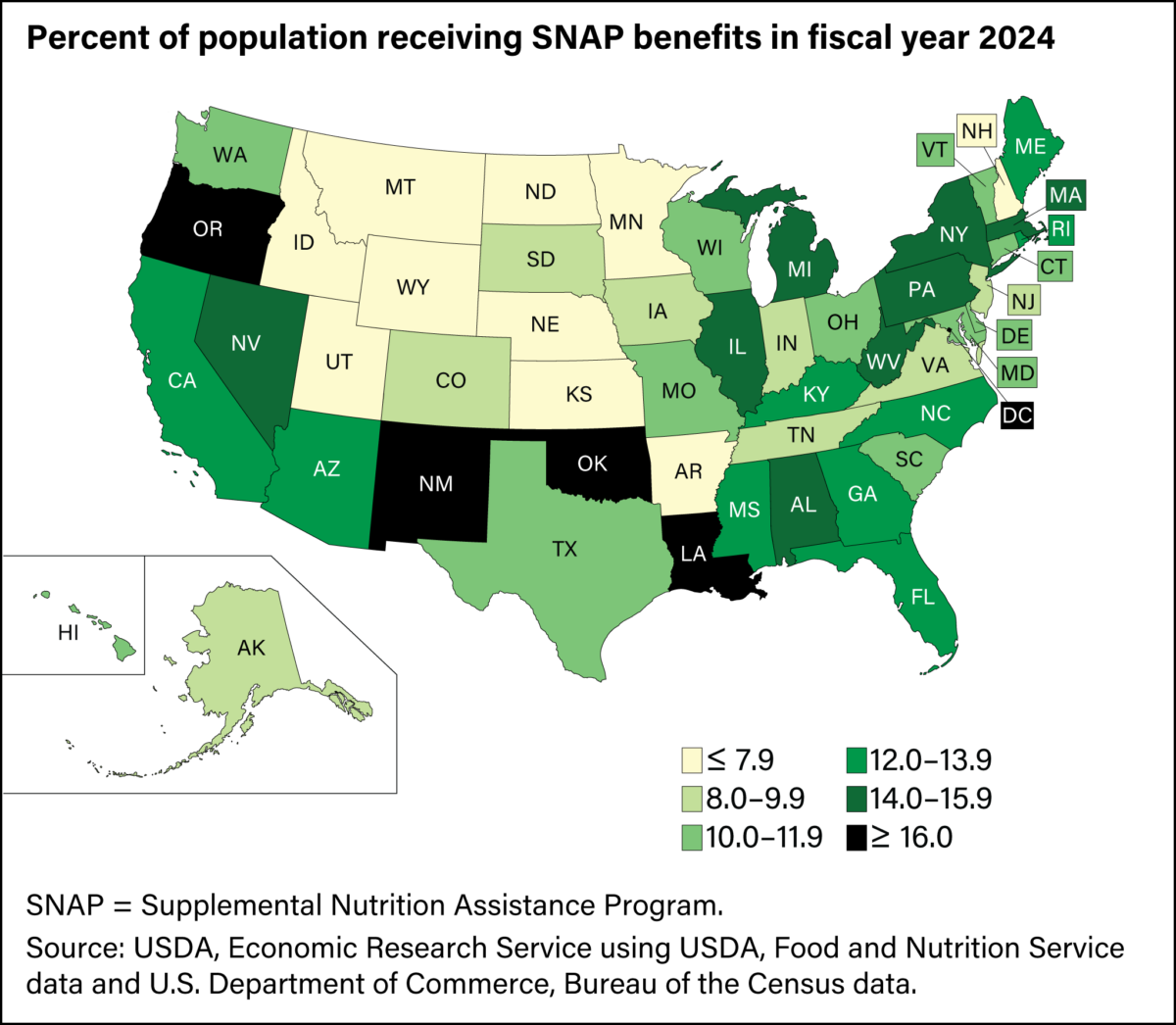

Nearly 18 percent of Louisianans rely on SNAP, one of the highest rates in the nation. The brief, historic lapse in SNAP funding exposed our country’s widening cracks. In places like Louisiana, where one in four children lives in poverty, the dismantling of basic support is a public safety threat to all.

Researchers at Clemson University found that every 1 percent rise in food insecurity is linked to almost a 12 percent increase in violent crime. Other national research shows that neighborhoods with lower food insecurity experience less violent crime and greater social cohesion. Studies also show that adolescents facing food insecurity are significantly more likely to engage in physical fights or risky behavior.

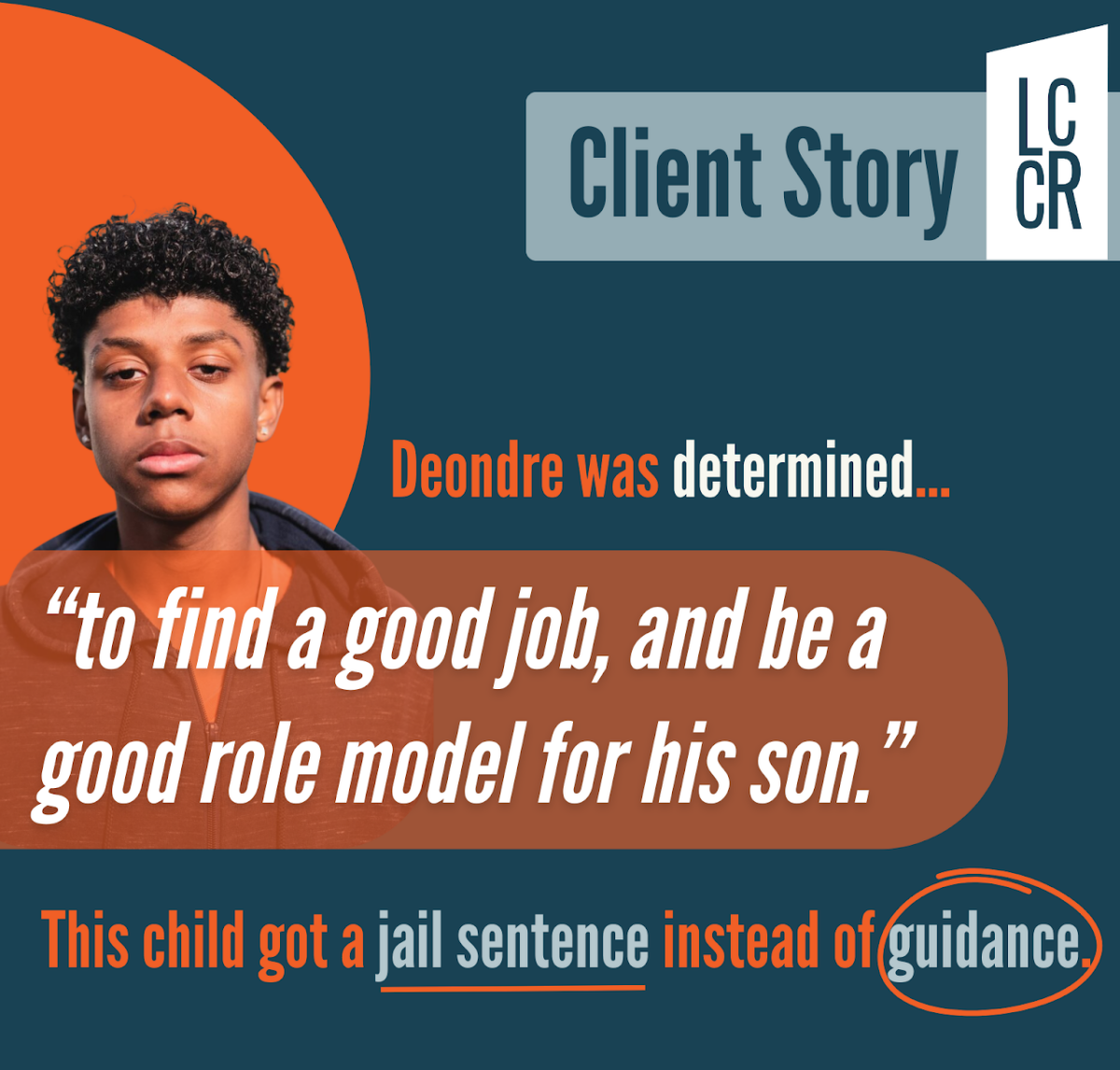

The Louisiana Center for Children’s Rights recently represented one such teenager, an 11th grader arrested for carrying a gun. He had been skipping school because he feared being robbed or killed while commuting through his neighborhood. He worked when he could to support himself and his young son while the two of them rotated between friends’ couches. He should not have had a gun, but it was a sign of desperation, not danger. What he needed was safety, a stable place to sleep, and enough income to feed his child. Once he secured those basics, everything changed for him, positively.

Stories like his are the often overlooked realities behind sensationalized headlines. It isn’t that hunger makes kids violent, it makes kids vulnerable—to stress, to bad decisions, to unsafe environments, and to systems that prefer punishment over support.

Programs like SNAP, on the other hand, have the opposite effect. Decades of research show that children who receive SNAP are healthier, do better in school, and are less likely to become involved in crime. In adulthood, those benefits translate into higher earnings and improved overall health.

Clearly, food provides more than nutrition. It creates the space for children and communities to reach their full potential.

I think back to teenage me, swallowed in an oversized blue shirt and an ill-fitting red hat, pacing behind the counter at McDonald’s. I was no more special or deserving than the kids I work with now. I simply had proximity to opportunity. A job nearby, a good school, and adults who stepped in where they could.

My outcome was circumstantial. But replicating those circumstances can be difficult, especially in the Bayou State.

Louisiana is home to the largest maximum-security prison in the nation. We applaud our government for filling prisons but question it for filling plates. We refuse to acknowledge that our children are mirrors whose actions reflect the conditions we have created: scarcity, instability, fear.

Crime is not the problem in Louisiana, where police data show that its largest city, once called the Murder Capital, is on track for its safest year since the 1970s. Declining conditions are. If we truly want safer streets, we need fewer empty refrigerators. We need a world where children don’t have to work night shifts or fear being robbed on the way to school.

The holiday season asks us to be generous, but generosity only goes so far when policy fails. We can keep locking up kids for the consequences of our neglect, or we can choose something radically simple: give them what they need to live. During this time of togetherness, that truth should not be controversial. Food is only the beginning.